Java Binary Code License Agreement

- Definition: Governs the use, distribution, and modification of Java binaries.

- General-Purpose Limitation: Free for general-purpose use; commercial license needed for specific applications.

- Free Uses: Development, testing, personal projects, open-source projects, educational purposes.

- Commercial Features: Java Flight Recorder, Java Mission Control, Advanced Management Console, and Usage Tracker require Java licensing.

The Java Binary Code License Agreement (BCLA) has been a crucial part of the Java ecosystem for decades. It governs how users can legally use, distribute, and modify Java binaries.

This article explores the history of the BCLA, its key terms, the implications of the general-purpose computing limitation, what is free under this agreement, and what commercial features trigger licensing requirements.

BCLA agreement can sometimes apply to Java employee metrics.

History of the Java Binary Code License Agreement

History and Evolution of the Java BCLA

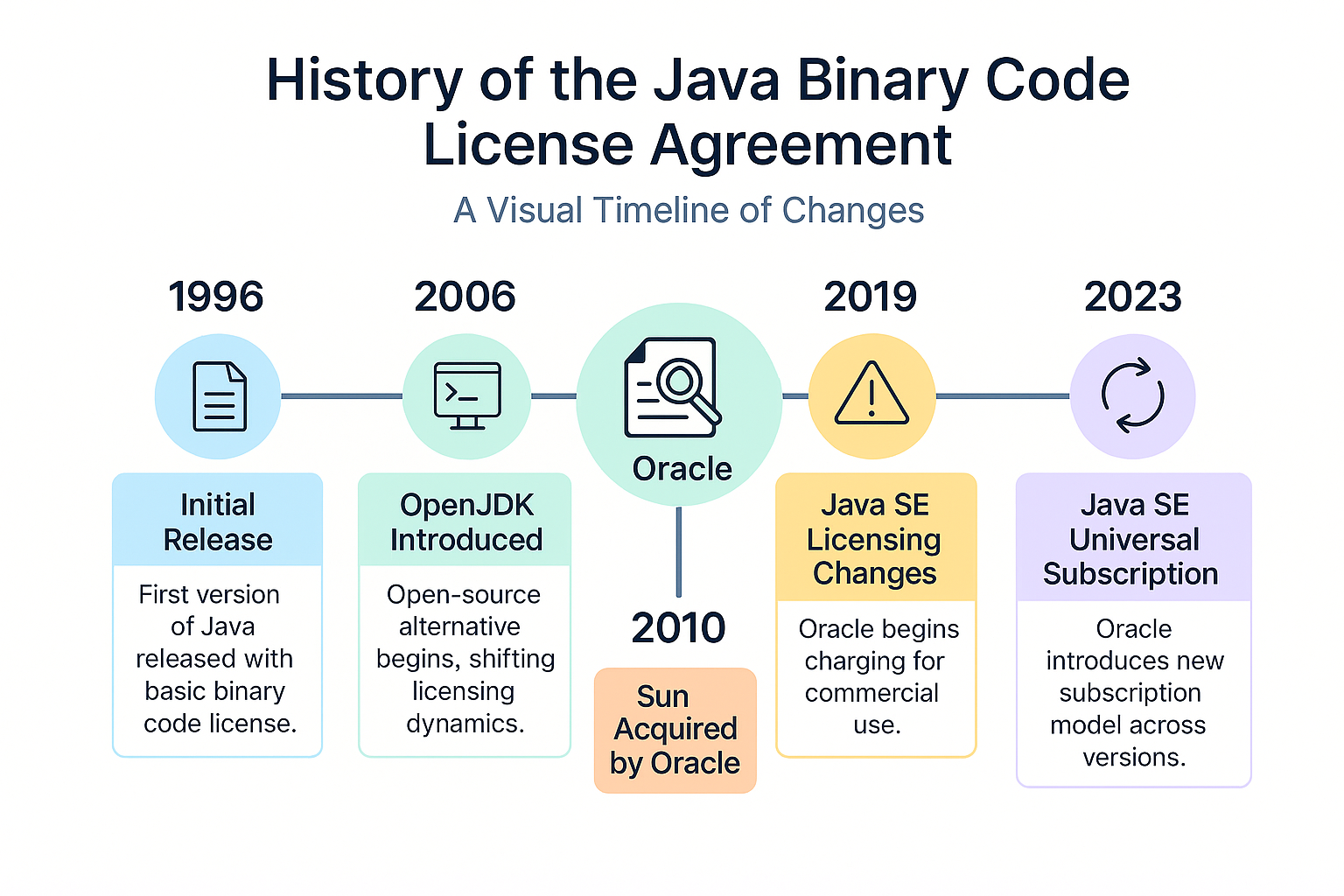

Figure: Timeline of Java licensing milestones – from Sun’s initial BCLA to Oracle’s recent subscription model.

Sun Microsystems introduced Java in the mid-1990s, and along with it came the Binary Code License Agreement (BCLA), which regulates the use and distribution of Java.

The BCLA ensured Java could be widely adopted while giving Sun (and later Oracle) control over how Java binaries were used.

Key historical points include:

- 1990s: Under Sun, the BCLA allowed Java’s free use for most applications, fueling Java’s popularity in enterprise and open-source communities.

- 2010: Oracle’s acquisition of Sun brought Java under Oracle’s purview. Oracle continued the BCLA but gradually aligned Java licensing with its commercial interests (e.g., introducing paid support and add-ons).

- 2019: Oracle retired the old BCLA model for new Java releases. Starting with Java SE 11, Oracle replaced BCLA with a new Oracle Technology Network (OTN) License. This marked a shift – updates for Java required a subscription for commercial use, and the free usage terms became more limited.

- 2021: Oracle introduced the No-Fee Terms and Conditions (NFTC) for Java 17 and later, making the latest Java versions free for all uses (including production) until the next long-term support release. This temporarily returned Java to “free for most users,” but only on the newest version and without long-term update support.

- 2023: A Java SE Universal Subscription model was launched, moving Java licensing to a per-employee subscription basis. This fundamentally changed cost calculations and prompted many organizations to reevaluate their Java strategy.

In essence, the BCLA era (Java 8 and earlier) permitted broad, unrestricted use, with certain exceptions.

Following 2019, Oracle’s licensing tightened, introducing significant costs for many who had previously used Java at no charge.

General-Purpose vs. Specialized Use: The BCLA’s Core Rule

The cornerstone of the Java BCLA is the “General Purpose Desktop Computers and Servers” clause.

In simple terms, Java can be used without fees on general-purpose devices, such as standard PCs, servers, or laptops, for everyday computing tasks under end-user control.

This covers typical business applications (email clients, internal business software, office tools) and constitutes the majority of Java use cases in enterprises.

However, the BCLA drew a line between general-purpose and specialized use. Java use was not free if it was part of a dedicated function or embedded system.

Examples of non-general-purpose (specialized) uses that fell outside the free usage clause:

- Embedded Systems & Appliances: Using Java in devices like network switches, industrial control systems, medical equipment, kiosks, or IoT devices. Embedding Java in hardware or firmware – for instance, a JVM inside a printer or a car telematics unit – was not considered general-purpose computing and therefore not covered by the free BCLA terms.

- Consumer Electronics & Mobile: Java running on mobile phones, set-top boxes, Blu-ray players, or other consumer electronics was explicitly excluded from the definition of a “general-purpose computer.” These uses required a commercial Java license or a separate embedded Java agreement.

- Function-Specific Software: If Java was bundled as part of a dedicated software solution (for example, an ATM software, point-of-sale system, or any closed-system software not intended for general computing), that usage fell outside the free scope. Oracle viewed this as using Java to power a specific commercial product or service, which triggered a license requirement.

In summary, under the BCLA, an organization could freely run Java for standard IT workloads and user-driven applications.

Still, if Java was used to power a special-purpose device or included within a non-general application, Oracle expected you to purchase a Java license for that deployment.

This general-purpose limitation was a critical distinction that enterprises had to evaluate to remain in compliance.

What Was Free Under the BCLA?

Under the BCLA (pre-2019 Java licenses), Oracle provided Java at no charge for a wide range of common uses.

Organizations did not owe Oracle license fees when using Java in these scenarios:

- Internal Development and Testing: Developers can download the Oracle JDK and use it to develop and test applications without incurring Oracle’s fees. An enterprise’s software engineering team writing Java code or running QA tests was considered free usage.

- General Business Applications in Production: Running Java-based applications on desktops and servers for internal business operations fell under the category of free, general-purpose use. For example, if a company built an internal tool in Java or ran open-source Java applications on their servers (such as a Jira server or Jenkins CI), they could do so under BCLA terms without a separate license, as long as those servers were general-purpose machines and not specialized devices.

- Personal and Educational Use: Individuals using Java at home or students and teachers in academic settings had free usage rights. Whether it was a hobby project, personal Minecraft mods running on Java, or a university using Java in computer science courses, the BCLA allowed it freely.

- Open Source Projects: Open-source software developers could include Oracle’s Java runtime with their projects (subject to certain redistribution rules) without paying fees, provided those projects were for general use. Many open-source tools and frameworks were built on Java under these terms.

- Redistribution for General Use: The BCLA permitted the redistribution of the Java Runtime (JRE) with applications, provided the application was intended for general-purpose computing and the Java components remained unmodified. For instance, an enterprise software vendor could bundle the Java runtime with their installer for convenience, under BCLA terms – but only if the end-user was installing it on a normal PC or server. (The vendor had to ensure end-users accepted the BCLA, and they couldn’t charge separately for Java itself.)

In essence, 95% of typical Java use in businesses was free under the BCLA.

Oracle intended to let Java proliferate widely for standard computing needs, ensuring compatibility and ubiquity.

No license purchase was required for most internal applications or user-facing software running on standard hardware, which is why Java became so ubiquitous in the enterprise world without direct licensing costs in its early decades.

What is Required by a Paid License Under BCLA?

Despite Java being freely available for many purposes, the BCLA spelled out specific scenarios where a commercial (paid) Java license was required.

Organizations needed to be aware of these to avoid compliance issues:

- Embedded and Industrial Use: If you embedded Java in a commercial product or device, you needed a license. For example, a medical device manufacturer that includes a Java Virtual Machine in its equipment, or a software vendor shipping Java as part of an embedded solution, would need to obtain an Oracle Java SE Embedded license. Similarly, Java running in hardware controllers, vehicles, ATMs, or any appliance meant that usage wasn’t free. This was a common pitfall – companies often didn’t realize that using Java beyond regular IT systems triggered licensing obligations.

- Commercial Software Products: Using Java within a software product that you sell or monetize generally requires a license. If a company developed a proprietary application in Java and sold it to customers (especially if Java was packaged with it or essential to its functionality), Oracle viewed that as a commercial use beyond “internal use”. The BCLA’s free terms didn’t cover “software made for resale or external users” without proper licensing.

- Enterprise Features of Java (Commercial Features): Oracle designated certain advanced components of Java as “Commercial Features.” Under the BCLA, these features were NOT free to use in production, even on general-purpose machines – you had to pay for them. Key commercial features included Java Flight Recorder (JFR), a low-overhead JVM monitoring and profiling tool. Using JFR to record production application data requires a paid license (Oracle Java SE Advanced or similar). Java Mission Control (JMC) is a GUI tool for analyzing Flight Recorder data and live JVM diagnostics. Using JMC in live environments requires a commercial license. Advanced Management Console (AMC): a tool for managing Java installations and updates across an enterprise. This management software was part of Oracle’s paid add-ons. Usage Tracker and others: Oracle’s JDK included flags and utilities to track Java usage – some of these also fell under commercial features. These features were bundled in the Oracle JDK download, leading to confusion. Developers could turn them on with a JVM flag (e.g., -XX:+UnlockCommercialFeatures in Java 8, but doing so in a production setting technically puts the organization out of compliance unless they had an appropriate license. Many firms inadvertently used JFR/JMC during troubleshooting, unaware that it wasn’t provided free of charge. Oracle’s audit teams became adept at checking server logs and configurations for evidence of these features being enabled.

- Large-Scale Enterprise Deployments: Even if not “embedded” in a product, an extremely large-scale deployment of Java in an organization sometimes led Oracle to argue that a commercial license was required. For example, if an enterprise packaged Java with an internal enterprise application and rolled it out to tens of thousands of desktops, Oracle’s sales teams might encourage the company to purchase a Java SE subscription or support contract (especially after 2019). Under BCLA terms, distribution within the company was allowed, but Oracle’s auditors would ensure that usage truly stayed internal and general-purpose (and that no commercial features were active).

To summarize, any use of Java that went beyond the ordinary “run my business app on a PC/server” scenario likely needed a paid license.

The moment Java was part of a device, a SaaS offering, or an advanced monitoring scenario, companies had to engage with Oracle for a commercial Java license.

Under the BCLA era, these licenses were typically sold as Java SE Advanced, Java SE Embedded, or Java SE Suite offerings, often on a per-processor or per-user basis.

Compliance and Risks for Enterprises Under BCLA

For companies heavily invested in Java, the BCLA’s restrictions meant that compliance required diligence.

Some key considerations and risks during the BCLA era:

- Software Audits: Oracle has a history of auditing its customers, and Java became a new focus area for audits in the late 2010s. If an organization unknowingly violates BCLA terms (for example, by using a commercial feature without a license or bundling Java into a product), an audit could result in substantial back-licensing fees or penalties. Companies needed to track where and how Java was used in their environment. This included maintaining records of Java versions, configurations (to see if commercial features were enabled), and distribution of any Java components.

- Cost Exposure: Although Java itself was free for most uses, non-compliance could result in unbudgeted costs. An audit finding unlicensed Java usage might force the purchase of Oracle Java SE subscriptions or support contracts retroactively. These costs could run into the hundreds of thousands of dollars (or more) depending on the scope. Even aside from audits, if a business intentionally needed to use Java in an embedded or advanced way, they had to factor in the licensing fees, which could be significant on a per-processor basis for high-end hardware.

- Understanding License Scope: The BCLA’s language was legalistic, and not all IT staff were aware of its nuances. This lack of understanding was a risk in itself. Developers and system administrators focusing on technical needs might, for instance, inadvertently activate a convenient tool like JFR during a production incident, thereby unknowingly creating a license obligation. Organizations had to educate their teams on what was allowed for free and what wasn’t. Clear internal policies (for example, disabling or password-protecting commercial features in the JVM by default) became a part of compliance governance.

- End of Public Updates (Java 8): Another risk emerged when Oracle ended public updates for Java 8 (the last BCLA-covered LTS version) in January 2019. Security updates for Java 8 and older became a paid benefit. Companies sticking with Java 8 had a choice: run without updates (a security risk), pay Oracle for a Java SE subscription to receive updates, or migrate to an alternative JDK provider. Many enterprises were caught off guard by this change, scrambling to budget for Java support or accelerate their migration to Java 11 or later (which introduced the new license terms).

In summary, during the BCLA’s reign, enterprises enjoyed considerable “free” Java usage, but this came with the responsibility to stay within the terms of the agreement.

Non-compliance risks ranged from legal exposure (violating license terms) to significant surprise costs if Oracle came knocking.

Oracle’s Post-BCLA Licensing Changes and Cost Implications

When Oracle moved away from the BCLA for newer Java versions, it fundamentally changed the Java licensing landscape.

It’s important to understand this evolution, as many organizations went from paying $0 for Java to suddenly facing substantial annual fees.

2019 – Introduction of Java SE Subscription (OTN License):

With Java SE 11, Oracle introduced the Oracle Technology Network (OTN) License for Java.

The key change was that using Oracle’s Java in production now required a subscription (for any commercial use beyond the limited free allowances).

While development and personal use remained free on paper, business use of Java 11+ effectively meant paying Oracle unless you switched to an OpenJDK build.

Oracle initially offered Java SE subscriptions on a per-user or per-processor basis (e.g., approximately $2.50 per user per month or $25 per server processor per month under the old model).

Organizations that wanted updates and support for Java 11 and later had to purchase these subscriptions.

The result:

Many companies started exploring alternatives, such as AdoptOpenJDK/OpenJDK builds (the open-source version of Java, which is free but without Oracle support). Those that stayed with Oracle’s distribution needed to include new Java subscription costs in their IT budgets for the first time.

2021 – Oracle No-Fee Terms (Making Java “Free” Again, Temporarily):

Oracle’s 2019 move caused considerable pushback and even defections to open-source Java. In response, Oracle announced No-Fee Terms and Conditions (NFTC) for Java 17, an LTS release.

NFTC made Oracle’s JDK free for all uses, including commercial production, for that specific version (and its minor updates) until the next LTS arrived.

For example, Java 17 under NFTC could be used in production at no cost through its lifecycle until Java 21 (the next LTS) comes out.

The catch was that once a new major version was released, any further updates to the old version would require a paid subscription, or you’d have to upgrade to the latest Java to remain free.

This approach was Oracle’s way to entice users to stay on Oracle JDK without immediate fees, while still steering them towards paid support in the long run if they didn’t keep upgrading.

Enterprises enjoyed a brief period during which deploying Java 17 didn’t trigger licensing costs; however, they remained cautious, knowing this could change with Oracle’s policies.

2023 – Java SE Universal Subscription (Per-Employee Licensing):

In January 2023, Oracle dramatically overhauled its Java pricing model again. All prior Java SE subscription offerings were replaced by a Java SE Universal Subscription metric that charges per employee (not per user or device).

This means that every employee in your organization must be counted and licensed, regardless of whether they use Java.

The license covers unlimited use of Oracle Java across the company, but the cost is tied to headcount, not usage.

This was a seismic shift, and for most companies, it significantly increased costs versus the old model.

Current Oracle Java SE Subscription Pricing (2023):

Oracle established tiered pricing, with volume discounts for larger companies.

Below is a simplified breakdown of the Java SE Universal Subscription rates:

| Total Employees in Company | Cost per Employee (per month) |

|---|---|

| 1 – 999 | $15.00 |

| 1,000 – 2,999 | $12.00 |

| 3,000 – 9,999 | $10.50 |

| 10,000 – 19,999 | $8.25 |

| 20,000 – 39,999 | $6.75 – $5.25 (sliding scale) |

| 40,000 or more | ~$5.25 or below (custom) |

Under this scheme, even a company with a small Java footprint but 5,000 employees must pay for all 5,000 users.

For example:

- A firm with 500 employees at $15 each owes about $7,500 per month (≈$90,000 per year) for Java licenses (even if only a handful of those employees actively use Java applications).

- A larger enterprise with 15,000 employees would fall in the $8.25 tier, paying roughly $123,750 per month (over $1.48 million per year) for the Java subscription.

These costs are orders of magnitude higher than the old licensing model.

Previously, under BCLA and even the 2019 subscription, a company might only pay for the specific servers or users that needed Java (maybe a few dozen servers or a few hundred developer machines).

Now, the cost is enterprise-wide.

Analysts have noted typical Java licensing bills rising 2x-5x for many organizations, and in some cases up to 10x, after this change.

Implications: This post-BCLA world means that companies must reassess their Java strategy. Paying Oracle’s Java tax is one approach (ensuring compliance but at a steep cost).

Others are migrating entirely to OpenJDK distributions (which are free and open-source, backed by vendors such as Red Hat, Eclipse Adoptium, and Amazon Corretto) to avoid Oracle fees.

Some organizations negotiate with Oracle for better terms or see if existing Oracle contracts (like database or middleware agreements) can cover Java usage.

The sticker shock of the per-employee model has made Java licensing a board-level discussion in many enterprises that previously took Java’s free availability for granted.

Recommendations

- Audit Your Java Usage: Conduct a thorough inventory of all Java installations and uses in your organization. Identify where Java is running (servers, desktops, applications, third-party products) and determine if those uses fall under general-purpose (free) or specialized (requires license) categories. This is the foundation for any compliance or cost decision.

- Avoid Unnecessary Commercial Features: If you do not intend to pay Oracle, ensure that advanced Java features (such as JFR and JMC) are disabled in production environments. Update internal policies and configurations to prevent developers or administrators from accidentally using features that trigger license requirements. For Java 8, this may mean starting the JVM with flags that lock out commercial features.

- Evaluate OpenJDK and Alternatives: To mitigate costs, consider switching to open-source Java distributions for your runtime needs. OpenJDK builds (from providers like Eclipse Adoptium, Red Hat, or Amazon Corretto) offer the same core Java functionality without Oracle’s licensing restrictions. Many enterprises have migrated their critical systems to OpenJDK to remain on free usage terms, particularly after Oracle’s changes in 2019 and subsequent updates.

- Assess Embedded and Third-Party Java Uses: If your products or hardware devices include Java, or if you use software from vendors that bundle Java, carefully examine these cases. You may need a license or to ensure the vendor’s license covers your usage. Reach out to software suppliers to confirm if they have distribution rights for Java in their product, so you’re not caught in between during an audit.

- Plan for Java Updates and Security: If you choose to stay on older Java versions under BCLA (e.g., Java 8), remember that free public updates are no longer available. Develop a strategy for handling security patches – whether that’s purchasing Oracle’s Java support for those older versions, using a third-party support provider, or upgrading to newer free versions periodically. Ignoring updates can lead to security vulnerabilities, but applying updates might inadvertently force you into Oracle’s newer licenses, so plan carefully.

- Budget for Compliance if Needed: If your analysis shows that you must use Oracle Java in a non-free way (e.g., a mission-critical system relies on a commercial feature or you cannot quickly migrate off Oracle JDK), then proactively budget for the appropriate Java licenses or subscriptions. Engage with Oracle (or an Oracle licensing expert) to get pricing and consider negotiating terms (especially if you have a large deployment – Oracle may offer discounts or custom deals for sizable commitments). It’s better to budget and negotiate up front than to face an unexpected bill in an audit.

- Stay Informed on Licensing Changes: Oracle’s Java licensing has undergone frequent changes in recent years. Assign someone (or a team) in your organization to monitor updates to Java licensing policies. For example, Oracle’s move to NFTC in 2021 or the introduction of the per-employee metric in 2023 caught many off guard. Being aware of such changes early will help you adapt your strategy (whether that means accelerating a migration, renewing a subscription, or leveraging a new free license offering promptly).

- Educate Stakeholders: Ensure that your development, operations, and procurement teams are aware of Java’s licensing constraints. Often, non-compliance issues start with a lack of awareness. Regularly communicate guidelines: e.g., “Don’t use Oracle JDK in production without checking with compliance,” or “We use Temurin OpenJDK for deployments – Oracle JDK is for development only,” etc. This reduces accidental exposure.

- Consult Licensing Experts if Uncertain: If your Java usage is complex or you’re unsure about your compliance position, consider engaging a software licensing consultant or legal advisor experienced in Oracle contracts. They can provide an independent review, help interpret ambiguous cases, and advise on negotiation tactics with Oracle. Given the high stakes (a large audit claim can reach into the millions), expert guidance can be worth the cost.

Checklist

- Identify Java Footprint: Create a detailed list of all applications, servers, and devices in your organization that run Java. Note versions and distribution (Oracle vs OpenJDK) for each.

- Categorize Usage Types: For each identified Java instance, determine if it’s a general-purpose use or a specialized/embedded use. Also, check if any commercial features are enabled. This will highlight areas where you may be outside of BCLA’s free scope.

- Review Contracts and Entitlements: Check if you already have Oracle agreements that cover Java (for example, some Oracle products include Java use rights). Verify any “Java included” clauses or vendor arrangements that might legitimize your usage.

- Decide on Licensing vs. Alternatives: Based on the above, make an informed decision – do you purchase Oracle Java licenses/subscriptions for certain uses, or do you migrate those uses to an alternative Java provider? For each use case outside free terms, have a plan (license it, remove/replace it, or accept the risk).

- Implement Governance: Establish controls and policies for Java going forward. This might include standardizing on a specific JDK for production (e.g., an open-source one), requiring approval to download Oracle JDK, regularly updating an inventory of Java usage, and training staff on these policies.

By following this checklist, you’ll have a clearer view of your Java licensing position and a proactive approach to address any gaps before Oracle flags them.

FAQ

Q1: Is Java still free under the old BCLA?

A1: Yes, for older versions and general-purpose use. If you are running Java SE 8 (or earlier) in typical internal business applications, you can use it under the BCLA with no license fee. The BCLA permitted these versions to be used freely for most standard computing purposes. However, if you use Java in ways that the BCLA restricts – like embedding it in a product, or using certain advanced features – then you would need to purchase a license for that usage. Also note that while running existing installations may be “free,” Oracle no longer provides free updates/patches for Java 8 and earlier. Therefore, the runtime is free, but maintaining its security may require a support contract or additional measures.

Q2: We only use Java on our internal business applications. Do we need to pay Oracle?

A2: Probably not, if it’s truly internal and general-purpose. Under the BCLA, using Java on “General Purpose Desktop Computers and Servers” for internal applications is free. So if your employees are running Java-based software on their PCs or your company servers for internal operations (HR systems, intranet sites, etc.), that’s covered by the free use terms. You do not owe Oracle license fees for that. Ensure that those applications are not special devices or externally provided services that would alter the classification. Keep in mind, though, if you have updated those systems to newer Java versions (Java 11+), the licensing rules differ (Oracle’s newer license might apply unless you switched to an OpenJDK). For pure Java 8 and below usage internally, you’re generally fine under BCLA.

Q3: What happens if we use a “commercial feature” like Java Flight Recorder without a license?

A3: If Oracle audits you and finds that you’ve been using Java Flight Recorder (JFR), Mission Control, or other commercial features in production without a license, they will likely consider it a license violation. In practical terms, Oracle could demand that you purchase a Java SE subscription or an equivalent license retroactively for those uses, potentially dating back to the first usage. This could mean paying for an Oracle Java SE Advanced license for each processor or server where it was used, possibly with back support fees. There’s also a risk of penalty fees or a requirement to stop using those features immediately. It’s not illegal in the criminal sense – it’s a contract compliance issue – but it can become very costly. The best approach if you discover unlicensed use is to stop using the feature and consult with Oracle or a licensing expert on how to rectify the situation (either by buying the needed licenses or removing the feature usage). Proactive disclosure vs. waiting for an audit is a strategic decision; many firms prefer to quietly correct course.

Q4: Can we keep using Java 8 for free, and what are the risks in doing so?

A4: Yes, you can continue to use Java 8 under BCLA for free, but there are two main risks: (1) Security and support: Java 8 no longer receives free public updates. Any critical security patches or bug fixes issued by Oracle after public support ended (January 2019) require a paid subscription. If you continue to use Java 8 without updates, your systems may be vulnerable to known security issues. Some organizations mitigate this by purchasing third-party support or transitioning to open-source builds (which sometimes backport fixes). (2) Future compliance: If your environment grows or changes (for example, you start deploying Java 8 in new ways that weren’t originally planned), you might inadvertently step outside the BCLA allowances. Oracle’s audits can also cover older versions. That said, using Java 8 in the same way you did before 2019 is generally license-free as long as you accept no new updates. The wise approach is to gradually migrate off Java 8: either upgrade to a newer Java version (with an open-source alternative or Oracle’s NFTC terms) or refactor away from Oracle JDK, so you’re not stuck on an outdated platform.

Q5: What options do we have if Oracle’s new licensing is too expensive for us?

A5: Many enterprises are asking this after seeing the 2023 per-employee pricing. Options include:

- Switch to OpenJDK distributions: The OpenJDK project provides free versions of Java that are essentially the same core code as Oracle’s JDK. Vendors such as Adoptium, Amazon (Corretto), Azul, IBM, and Red Hat offer tested builds with either free or more affordable support models. By migrating your Java installations to these, you avoid Oracle’s fees entirely (though you might pay a smaller support subscription to a vendor if you want long-term patches).

- Use the Oracle NFTC for the latest Java and upgrade frequently: Oracle’s No-Fee Terms allow you to use the latest Java version in production without cost. The catch is that you must be willing to upgrade to each new major version as it becomes available (typically every year or so for Long-Term Support, or LTS, versions) to stay on a freely supported version. This can work if your applications can keep up with Java upgrades, but it shifts the operational burden to your team.

- Negotiate with Oracle: If you have a substantial Oracle relationship (such as a database or middleware contract), you may be able to negotiate a custom deal for Java. Oracle sometimes provides concessions or bundles Java as part of a bigger agreement. You’ll need executive-level negotiation and possibly help from licensing advisors.

- Limit Java usage where possible: Evaluate whether all Java installations are truly necessary. For example, if certain applications can be decommissioned, replaced with non-Java solutions, or consolidated onto fewer servers, you reduce the scope that needs licensing or migration. In the extreme, some organizations consider replatforming applications away from Java to eliminate the dependency (this is a long-term and costly approach, only for critical cases).